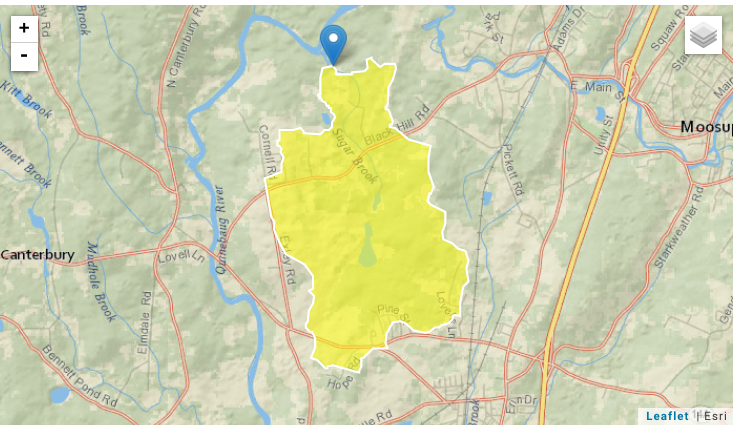

This article will be addressing the current processes occurring in my local watershed in Sprague, CT that are used to protect and restore the watershed and discuss these best management processes (BMPs). The local watershed is called Little River, there are several streams and rivers in this watershed, and throughout the watershed, there are about 42.8 square miles of land that drains into these streams as shown in Figure 1. and Figure 2. (Streamstats, n.d), we also see in this figure that 6.22 percent of the land is developed around Little River.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Around my local area, there has been little strategic building in order to better protect the watershed in recent years. In the area, we have several business plazas in the neighborhood, as well as a park so there is a lot of developed land. However, with the park, there are a lot of trees that are conserved in order to keep the beauty or aesthetic of the park. There’s also foliage near the roads that although they get trimmed back commonly, they aren’t removed from the area. This is unfortunately the most that the community has really been doing in terms of building strategically. With most of the roads paved, and many homeowners switching to paved rather than dirt or gravel driveways we are switching to more of the impervious covers. Although the only good side to this is that there hasn’t been much more development in the general area than that, businesses have come and gone but in the same building; There hasn’t been any more land cleared for newer buildings or extremely large and unnecessary parking lots.

If I had to suggest any ideas in order to strategically build better, I would certainly suggest that we incorporate more land preservation than we are already currently doing, and also express the importance of it to neighboring towns that might be doing more development than us. We could also choose to minimize our lots that aren’t being used as much, in order to give the opportunity for nature restoration – if the lots aren’t being used very often there is no real point in continuing the impervious cover that they provide. Finally, we could also encourage and incorporate more open space designs in neighborhoods and stop constructing culdesacs as often. By building more open concept communities we could minimalize our impact on watersheds and the overall environment, which will prove to be beneficial to us at the end of the day (Better Site Design, 2019).

Another management practice you can see quite commonly in my local area to assist the protection of my watershed is the usage of non-stormwater discharges. Sewer grates can be seen all over where I live, and these can help since during a storm when you see all the water gliding down into these grates, they are collecting all the water into a pipe under these grates, that water is then transported to a municipal treatment plant. The goal of this plant is to remove the pollutants from the water in turn making it more sanitary (Environmental Protection Agency, 8 Tools of Watershed Protection in Developing Areas). This can be a win or lose situation though since there are many cases when there have been significant waste reduction rates, however, it usually comes with the threat of more development of land as well as the risk of something going wrong, such as overflows.

Another form of non-stormwater discharges present in my area is the usage of septic systems, which I am sure many of us are familiar with but these basically take the waste from toilets, bathtubs, etc. and treat as well as discharge the water from them (Environmental Protection Agency, 8 Tools of Watershed Protection in Developing Areas). These systems are in the ground, however, and a problem that can occur occasionally is, unfortunately, should the septic system fail, it can pollute the water nearby in lakes, rivers, or just the groundwater in general.

These BMPs are very important to keeping the integrity of the watershed intact because although Little River is relatively clean compared to many other watersheds, it still is polluted and needs to be improved. Our watersheds are very crucial to our environment, but luckily with courses like these, we are becoming more informed on how to proceed in the future and conduct better research on them.

Reference:

Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). 8 Tools of Watershed Protection in Developing Areas. EPA. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://cfpub.epa.gov/watertrain/moduleFrame.cfm?parent_object_id=1341

Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). National Menu of Best Management Practices (BMPs) for Stormwater-Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination. EPA. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://www.epa.gov/npdes/national-menu-best-management-practices-bmps-stormwater-illicit-discharge-detection-and

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. (2019, September 27). Better Site Design Better Site Design. Better site design – Minnesota Stormwater Manual. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://stormwater.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/Better_site_design

StreamStats: Streamflow Statistics and Spatial Analysis Tools for water-resources applications active. StreamStats: Streamflow Statistics and Spatial Analysis Tools for Water-Resources Applications | U.S. Geological Survey. (n.d.). Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/streamstats-streamflow-statistics-and-spatial-analysis-tools